By Felix Salmon

Back in December, Max Baucus, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, came out with a pretty bold proposal to simplify America’s energy taxes, and to focus them on a simple goal: that the US should emit less carbon. That should be a pretty easy thing to do, in theory: you just raise taxes on the more carbon-intensive energy sources, while not raising them, or even cutting them, on sustainable energy sources. Except that’s not the way the US tax code works. America, it turns out, doesn’t really tax energy at all: instead, it subsidizes energy. And the amounts of money involved are very large:

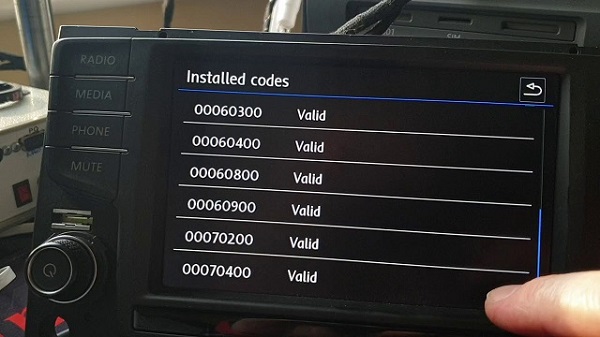

Under current law, there are 42 different energy tax incentives, including more than a dozen preferences for fossil fuels, ten different incentives for renewable fuels and alternative vehicles, and six different credits for clean electricity. Of the 42 different energy incentives, 25 are temporary and expire every year or two, and the credits for clean electricity alone have been adjusted 14 times since 1978 – an average of every two and a half years. If Congress continues to extend current incentives, they will cost nearly $150 billion over 10 years.

As a result, Baucus can’t simply tweak energy taxes; instead, he has to tweak energy subsidies. His proposal is a good one: he essentially consolidates all those 42 existing subsidies into two new ones — one for electricity, and one for transportation fuel. In both cases, tax credits get handed out in direct proportion to how clean the facility is. Once carbon emissions have reached 75% of their current level, the subsidy phases out.

Charles Komanoff, of the Carbon Tax Center, responded to Baucus’s discussion draft last month, in testimony to his committee. Komanoff’s paper is conceptually simple: he asks what the outcome would be if instead of subsidizing clean energy, the government decided to go ahead and tax carbon emissions directly.

The first big difference, of course, would be fiscal. Komanoff takes 2024 as his base year, and reckons that under the Baucus plan, the government subsidies will cost taxpayers some $39 billion in per year, in ten years’ time. A carbon tax set at roughly the same level, on the other hand, would generate a whopping $450 billion per year in fresh government revenues. That’s enough money to make the system progressive, rather than regressive: checks could be sent out to lower- and middle-class households to cover any extra expenses they suffered as a result of the carbon tax. The Baucus proposal, by contrast, is regressive: most of the benefits would end up flowing to the highest-income households with the highest energy use.

The other big difference is in carbon emissions. Here’s Komanoff’s chart:

A carbon tax, by its nature, affects everything: it’s applied equally to every sector of the economy, and encourages energy conservation (turning your thermostat up a little in the summer, for instance) just as much as it encourages cleaner energy creation. Komanoff’s model assumes a carbon tax which changes exactly as the Baucus subsidies do. Baucus’s tax credits work out at about $55 per ton for eliminated electricity-related carbon, and $102 per ton for eliminated carbon in the transportation sector. Komanoff’s carbon tax is set at just those levels for those industries, and at the average of the two everywhere else; overall it works out at a high $78 per ton. (Which serves to demonstrate how generous the Baucus proposal is.)

The problem is that there’s no easy way to get there from here. Fiscal policy is path-dependent, and Baucus knows full well that it’s hard enough to take one group of subsidies and replace them with two new subsidies which go to the same industries and cost roughly the same amount of money. In the current Congressional climate, it’s downright impossible to take an existing group of subsidies and replace them with a brand-new tax. Doing that would be wonderful in terms of reducing carbon emissions, but it would generate so many squeals of pain from the energy lobby (not to mention Republicans who hate all new taxes on principle) that it would never even get as far as a vote.

President Obama has said that addressing climate change will be a top priority of his second term — but he said that it would be a top priority of his first term, too, and he did exactly nothing on that front in his first four years. I doubt that Komanoff’s testimony came as any surprise to Baucus: it’s a well known fact in Washington that a carbon tax would be an extremely efficient way of raising much-needed revenues, reducing US carbon emissions, and helping America achieve energy independence. But Washington is not a town which tends to embrace efficient or logical solutions. If we’re going to reduce carbon emissions any time soon, we have a much higher chance of doing so with carrots than we do with sticks. Even when the sticks are much more effective.